How the Goan Lost His Art

Vivek Menezes examines why the story of Goan art is intertwined with a strong streak of sheer cussedness.

Better had I died,” said Francis Newton Souza about his disfiguring childhood bout of smallpox. “Would have saved me a lot of trouble. I would not have had to bear an artist’s tormented soul, create art in a country that despises her artists and is ignorant of her heritage.” (Words and Lines, 1957.) This despairing plaint was written when the artist was still only 33 years old, and already nearly eight years into an ambitious but hardscrabble exile, in slow transit from London to Paris and back again.

The bitterness, the anguish was entirely understandable. It had taken a kind of superhuman determination and grit to merely get to the cultural capitals of the West -- most of Souza’s savings accrued in small pots, from dances and concerts organised for idle British armymen. The bravado of the Saligao boy seems outlandish in retrospect, even in our age of NRI ballyhoo – he was determined to make his place among the great modern artists of the world, and that was going to be that.

Everyone but his mother laughed at him. Obviously there was no way that Newton was going to be a great artist, because great artists do not come from Saligao, with smallpox marks all over their face. He was expelled from St Xavier’s School. He was expelled from the JJ School of Art. The police threatened his first show (each painting sold for Rs. 51!) because someone complained about the nudes. It was an exhausting, constant struggle on the fringes of respectability. He stood on the threshold in this manner all his life, a tense waiting game that was resolved only after he was in the grave.

In today’s era of endless hype and soaring auction prices that routinely top a million dollars, it’s essential to remember that Souza’s paintings sold for negligible sums of money all through his long career. And, for a good part of that time, his art was pilloried, and very often treated as faintly disreputable by the very same establishment that now gushes triumphantly about “The Masters”.

Souza’s harrowing tale isn’t very unusual at all – the same treatment has been meted out, with metronomic regularity, to each generation of Goan artists. The ‘enfant terrible’ was forcibly shunted to the sidelines; the serene visionary Vasudeo Gaitonde was ignored and almost wilfully misunderstood. You look at Laxman Pai’s work and see genuinely superb paintings in one style in one era, and an entirely different style in another, and you detect how he was harried, driven to a state of almost schizophrenic, compulsive adaptation.

The urge to fit in, to belong, is the Achilles heel of the Goan original – the narrative arc of modern Goan art traces a shabby, ill-fated, desperate struggle for acceptance and recognition on its own terms. It has never come; the irony in our fate is that we keep looking for it.

No case is more egregious, or, indeed emblematic, than that of India’s towering lost modernist, Angelo de Fonseca. Born the youngest of 17 children, to a wealthy land-owning family from the island of Santo Estevao, he set off to become an artist in the teeth of vociferous opposition. Even worse, from his family’s perspective, the young grandee had no interest at all in the one recognized institution, the JJ School of Art, where another pioneering Goan artist, Antonio Xavier Trindade, had become faculty member in 1921.

No, Fonseca found JJ unsuitable. In his own words “there was still a European principal. I wanted to become a sisya of the best Indian artist in the twenties of this century. Accordingly, I went to Santiniketan.”

An examination of Fonseca’s earliest works from Santiniketan reveals a profound intelligence already worrying away at the margins of what would become a brilliantly original style.

There is a strongly fired sense of kinship, evident in stunning, characterful portraits of ‘Guruji’, Rabindranath Tagore, and his nephew, Abanindranath. The waves that swept through Santiniketan in that era each had its impact – Fonseca worked to absorb Mughal tradition, to take in influences from Japanese and Chinese art. Later, Nandalal Bose gave the young Goan a valuable grounding in the traditional Indian use of form and colour. The work from this period is steeped in ambition: Fonseca was building to something but the object of desire remained unknown.

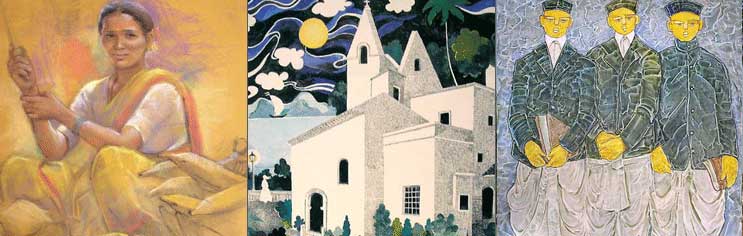

Direction came forcefully and all at once. Abanindranth Tagore said, “Go back, young man, and paint the churches of your land.” And as a sisya must, Fonseca obeyed and headed straight back to Santo Estevao, to build his future. It was an ill-fated move, in an era of profound communal mistrust and colonial paranoia.

You look at the paintings now, and you marvel at tremendous growth and steadily increasing mastery over medium and materials. But Fonseca was being hounded at each step at the same time, denounced from his own parish pulpit for contradicting the imported icons of the Portuguese.

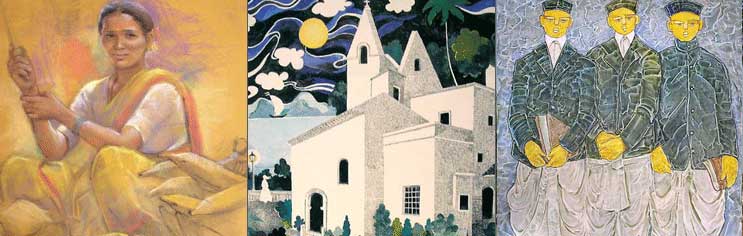

Depict the Madonna as a Goan woman? Paint the labourer class with dignity, even nobility? The clamour of disapproval became total, and increasingly hysterical, even as Fonseca clung to his ideals. He continued creating a stunning oeuvre of very Goan paintings that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the most important modern Indian art – organically from the soil to the point that the colours are literally mixed with the talismanic, very red earth of his native land. He was now faced with the same plight that has faced our best artists in each generation. Stay in Goa in relative peace but toe the line, or leave in order to develop your own original voice.

Fonseca made the same choice that Souza made after him, that Laxman Pai was cornered into later in the 20th century, which still weighs on the mind of the seriously talented artists that our culture continues to unknowingly throw up.

He left. He sought appreciative company where he could get it (Veer Savarkar’s rightist clique, foreign priests, the fiery Jesuit nationalist H. O. Mascarenhas), and a grim determination started to emerge in his works that bears another strong parallel to Souza’s trajectory.

For the story of Goan art is intertwined with a strong streak of sheer cussedness, a hang-the-consequences attitude that emerged, perhaps inevitably, after a thousand slights and cuts.

No matter how great the Goan artist – and they don’t come greater than Fonseca, Souza and Gaitonde – he has had to make a decision to soldier on against terrific odds. He tends to find himself foundering, in an interminable waiting game, always seeking approval and acceptance from constituencies which never share it willingly.

Fonseca was too Indian for colonial toadies, even for his own family. Souza was too bold and impatient, too Goan for the Indian cognoscenti. And Gaitonde was so far ahead of his time that we’re still racing to come to grips with what might be the most eternal work of any Indian artist in the 20th century.

In all these cases there is a decisive moment, and then a certain hunkering down with only posterity in mind. At some separate point in each man’s troubled life, there came an exactly similar moment of clarity, a reckoning resolved in the same manner.

You see it in the paintings – Souza, Gaitonde and Fonseca each stopped fussing about the recognition that was destined to elude them in life. And then they set off with clenched teeth, to play for very high stakes indeed. They consciously take on the immortals; they overtly set themselves against and among the greats.

Immensely moving to witness now on canvas and paper, the contemporary observer stands humbled and contrite in front of these highly ambitious masterworks that languished unrecognised for so very long.

In this, also, Fonseca’s case stands out as particularly egregious, if somewhat redeemed by the single-minded fidelity of his widow, Ivy. Chased from his homeland, he found the Church set against him even in post-1947 India. The Catholic newspaper, The Examiner, ran articles denouncing him as ‘pagan,’ though approval from a small coterie of churchmen provided some solace before he died largely unrecognized in 1967, just a few years before Vatican II and its perhaps temporary glasnost towards indigenous expression.

Steadfast to the end, jaw firmed by that hard-earned determination, he stuck to his life’s question: “Why should not the Catholic Church find herself at home in India, when she is really Catholic, i.e. universal, Indian in India as she is in Europe?”

Back to the art, which we can perhaps look at with a certain dispassion born from the passage of time, and the churning of history in what seems to be our direction. What we have, what the Goans have produced in the contemporary era in an unbroken line (from Trindade through Fonseca to Gaitonde, Souza and Pai and on to Antonio e Costa and Viraj Naik) is monumental even while it remains woefully misunderstood. The common threads of narrative exist for a re-assessment, but it has not been attempted until now.

Souza has long been appropriated by one narrative, now popular with auction houses and brand new galleries in San Francisco and New York. Gaitonde is mired in yet another, still forcibly separated as if by glass from his very evident cultural roots. Fonseca, as we have learned, is still unconscionably abandoned; his paintings ignored even as vastly inferior contemporaries (like the two-dimensional Jamini Roy) are shoehorned undeservingly into the limelight.

All along, there is a total, unbending denial of their essence of being, of their Goanity, of what is referred to lovingly in Konkani as ‘goenkarponn’.

It is a kind of existential threat – deny Souza’s irrepressible Goanness and you deny the reality of his life and strivings. Deny Gaitonde his context, and lifelong steel-cabled bond with Souza, and you forcibly manipulate a cherished Genesis story of modern Indian art. Deny the very existence of the towering genius of Angelo de Fonseca, and you deprive an entire culture of self-knowledge and the fertile soil required to grow anew.

Goa stands bereft and deeply impoverished, we have betrayed our artists and still fail to understand our spectacular heritage.

Santayana famously predicted that “those who forget history are condemned to repeat it.” But what do we say about a people that has forgotten its art, that continues busily forgetting even as generations pile up on generations, that’s hard at work to forget young artists even as they work today?

Imagine Bengal without any appreciation of Tagore. Think Spain, but without Goya. Now look around at Goa, where a full ten out of ten people on 18th June Road or, indeed, in the Central Library, will be entirely ignorant about Souza or Gaitonde or Antonio Xavier Trindade.

Perhaps even worse, check the reactions of the Indian cognoscenti if you so much as use the words “Goan art”. Eyes roll, noses upturn. “Is there such a thing?” “Souza, yes, but he was from Bombay”. “Gaitonde isn’t Goan, he wasn’t born there.” “Angelo who?”

It’s the Goan destiny, we all eventually have to turn away from the world, and look intensely at what we have and what we are, and appreciate it all on our own terms. No one “gets us” the way we would like, probably because no one can.

Goa has represented the shimmering horizon, the land just before the unknown, all through recorded history, and there is an undeniably fluid quality to our culture, character and art that is hard to understand from any kind of blinkered perspective.

It comes from a space that has always balanced elegantly between opposing forces, recognisably Eastern to Westerners, yet with the opposite also entirely true. The world has never been able to understand the many-layered Goan identity, and we’ve run from it many times ourselves. But still the art speaks; still the paintings of our masters strike home.

Recently, after a struggle, an Angelo de Fonseca oil painting was rescued from destruction. In its rough-hewn wooden frame, it had lain in a rubbish heap for several years. There is still grime embedded on the little canvas. Placed on a wall for the first time in decades, it glowed incandescent. An even-featured Goan girl, veil drawn modestly over her head, eyes downturned. She is divinity, village belle, virtue personified. Hypnotically beautiful on the canvas, there is a secret embedded – the lovely face is alive with a wonderfully delicate light, from an unseen candle. “It is more beautiful than the Mona Lisa,” said the man who saved this masterpiece, spontaneously. Then, more quietly, “It is our Mona Lisa.”

And so it is. Take a look at the cover of this catalogue.

(Courtesy: Goa Tourism Development Corporation.)

|